Here we give a few tips and pointers to make sure that you are driving an electric car that makes a discernible reduction to your personal carbon (and other emissions) footprint.

Charging your electric car

There’s an old cartoon of a smug EV driver plugging their car in to a socket, with a cable running from that socket to a power station billowing out smoke. The thing is, it’s basically rubbish.

For starters, the UK’s electricity mix - the percentage of sources the electricity is generated from - is getting greener all the time as renewable energy sites increase or expand. There is basically no coal being used - and in fact there have been increasing periods of time where no coal has been burnt for months on end. At the time of writing, only 3% of the electricity mix was from coal, which isn’t at all bad for a winter’s evening with low winds.

Now, gas is the largest generator, with around 40% of the UK mix on average. Renewable energy. - from solar, wind, or hydro-electric - accounts for more than 30%, but the make-up of this clearly greatly depends on weather conditions; solar is less prevalent in the winter clearly. “Other” makes up the rest of the mix, which is primarily nuclear at 10-15% of the mix, with bio-mass, and stored energy making up the rest of grid.

But it is easy for an EV driver to drive on clean energy all the time. Domestic electricity tariffs are easy to find that are backed by renewable energy guarantees, and the majority of the UK’s public charging networks also use green energy. With very little effort at all, you can drive an electric car on clean energy.

Whole life emissions

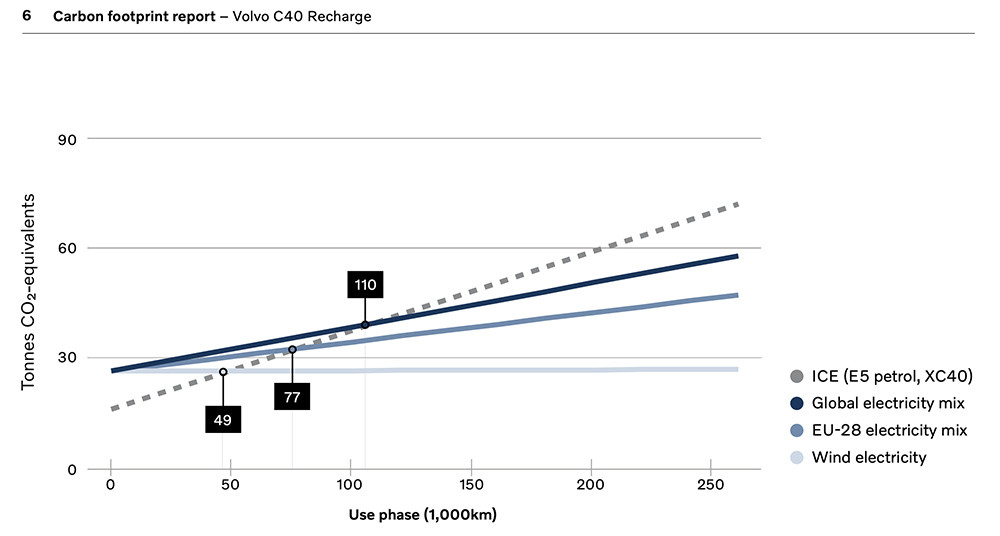

Graph courtesy of Volvo Cars

To truly analyse an EV’s impact on the environment, it’s important to not only look at the emissions produced at the wheel, but the whole life cycle. Driving along, as we’ve found out above, an EV can produce zero emissions when powered by electricity generated be renewable electricity.

There are tiny amounts of brake dust and tyre particles, but these are less than or similar to those of a petrol or diesel model. Tyres are the main difference, because electric cars are heavier than conventionally powered counterparts. But EV tyres are designed to have low rolling resistance for improved efficiency, so inherently there are fewer bits and pieces being shredded off them when driven along than compared to grippier rubber.

And brakes; yes EVs are heavier, but the brakes are used far less frequently. In fact brake wear is such that often parts need to be replaced because they have got too old or weather beaten, rather than too much has been worn away because of friction braking.

But one area EVs do significantly fall down compared to petrol and diesel models is in the manufacturing process. An electric car doesn’t need an engine or multi-ratio gearbox, nor does it need numerous lubricants and cooling liquids. But what it does need is a huge battery, which is resource heavy to manufacture both in the manufacturing process and the materials used.

As such, electric vehicles start life having rolled off the factory floor with an emission-based disadvantage to petrol and diesel models; they have consumed greater levels of materials and energy to create, distribute, and put together.

However, the ability to run largely emission free means that there is a point when the EV’s lifetime emissions crossover that of an internal combustion vehicle’s and will remain lower. The crossing point depends on the EV, the driver, and the number of miles covered. The more electric miles travelled each year, the sooner the EV will cross that threshold and become the greener model.

“Right-sizing” your EV

For many drivers, to be persuaded into an electric car, it needs to go two, three, four hundred miles on a charge. But is really doesn’t. The average trip length in the UK is less than 20 miles, and daily routes for many will comfortably be less than 100 miles round-trip.

Rarely will a driver cover more than 150 miles without stopping, and even then, require even greater distance without the chance to recharge. So you should think, what mileage do I actually need?

The issue here is often for those that are getting an EV as their second or third car, because this indecision, this persuading required means they are not committed to electric cars and happy to life with their inconveniences.

So if you still have a petrol or diesel model, why not have an EV that will take the strain for the 95% of your year’s journeys and cover around 100-150 miles on a charge. Most households will still only need to charge their car once a week with a car offering a range of 150 miles on a charge.

And the benefit here is that a shorter range comes from a smaller battery. Not only does this make the car more efficient because there is less weight to be carried around, it also makes recharging faster and… here’s the crucial bit - uses fewer resources.

So by all means pick a car with a 250-300 mile range if that’s your main vehicle. But if this is a car that will do the regularly weekly routes - regular, within a short distance of home or familiar routes - why not get a vehicle with a smaller battery and have a “better” car?

Drive efficiently

There are a range of features that can help get the most from your EV’s range, and if you maximise that, it requires fewer recharges, the battery lasts longer, and the energy used is less.

So the Eco button can help restrict throttle input, easing you forward rather than shooting you forward. But the key area of improvement is the brake energy recuperation system. It’s a way of charging the car’s battery when slowing down or going down hill, inverting the energy flow and using the wheels to turn the motor and make it act as a generator

Almost all EVs have at least a D and a B setting - weak and strong regen - and many have three or four stages to pick from. Auto settings can work well to help out, but experienced EV drivers can do more with manually selecting the setting themselves. And don’t just pick the strongest setting and leave it there - switch between them in a similar way that you would change gears in a manual.

At higher speeds, such as on motorways and dual carriageways, coasting can offer greater levels of efficiency than slowing down and recuperating energy into the car’s battery. But at slower speeds - in traffic, along country roads, in hilly terrain - switching between the settings will give you greater miles per kWh used. An EV is an easy car to drive, but to be efficient requires a bit of concentration.